Zenith 6D413 (6-D-413) Restoration

|

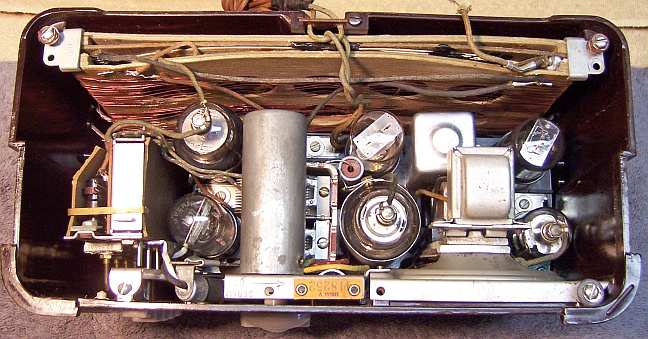

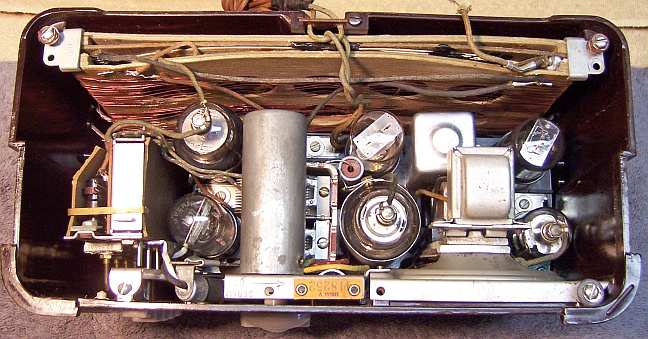

The Zenith 6D413 from 1940 is a 6-tube (5 tubes plus ballast

tube) AC/DC Superhet

circuit radio that

receives only the broadcast band. At first glance, the radio had seen no obvious servicing

(other than tubes) in the past and all

of the original

parts appeared to be still in place. I

decided to try to restore the the radio and maintain the original chassis appearance if

possible. The model number was not confirmed, since there was no model

number or chassis number found - only a serial number tag.

The schematic and a parts list for the radio can be found on Nostalgia

Air. Any part number references in the text below reference that

schematic. |

My

antique radio restoration logs

Overview

According to an excellent article found at http://www.uv201.com/Radio_Pages/zenith_bakelite.htm,

in 1940 Zenith introduced a line of radios that featured a molded bakelite

chassis. The chassis was mounted upside down in the cabinet and the tube

sockets, volume control, one IF transformer, trimmers as well as some fixed mica

capacitors, and other

components were molded as integral parts of the chassis. These radios were

troublesome from day one, and they were almost impossible to work on. Most

were recalled and destroyed. These models only lasted one year, and I'm

sure some heads at Zenith did roll for this blunder!

My example was purchased on eBay and listed as not tested/not

working. The AC line cord had been cut off. Externally it appeared to be all

original, complete and in excellent condition. There were no cracks or breaks

in the cabinet. The chassis is

small and quite compact, and access to parts is limited and difficult. There

are hair thin wires exposed under the chassis coming from the first IF transformer

and from the oscillator coupling coil. These components have few or no

terminal lugs, and wire ends from the windings are connected to other points on

the chassis. Damage is possible unless extreme care is taken.

I had previously restored a Zenith

model 4K-402D, a four-tube battery portable that uses the same bakelite

chassis construction.

Prior Servicing

I always attempt to avoid purchasing radios that have been

"restored" by collectors or flippers, and am looking for either all

original examples or those which have been "lightly serviced" in the

distant past by radio service shops. In this example, almost all of the original

parts were still in place. The only non-original parts I found were

one resistor, some of the tubes, and the pilot lamp. The 35Z5G and 35L6G tubes had been replaced with GT type

tubes. The 12A8G, 12K7G, and 12Q7G tubes were all the correct types, were

branded Zenith and were

good. The 12K7G and 12A8G were date code "X 9Y" (1939?) and likely

OEM. The 12Q7G was

date code M0R, indicating 1940 and a replacement. The ballast

tube was an Amperite, and possibly original.

Survey

My usual restoration procedure is to first make a complete

survey of the condition of all components. The survey results guide my

restoration strategy. I never apply power to a radio before

restoration. If major and unique components are defective or missing and cannot

be restored or replaced, I may elect to sell the radio rather than restore it.

I always assume that all paper and electrolytic capacitors are leaky and thus

should be replaced (I normally "restuff" the original containers if

possible). Survey results:

-

All tubes tested good.

-

The speaker was OK.

-

The output transformer was OK

-

The filter choke was OK

-

The oscillator coil and oscillator coupling coil were OK

-

The IF transformers were OK.

-

The dial lamp was OK but was the wrong type (#44 vs. #47)

-

The line cord was had been removed and the fiber entry board

was broken.

-

One resistor, R4 (2.2 meg) had been replaced by a 170K

resistor - old style dogbone resistor! This was likely an older

repair. I'm not sure what effect this change would have had to the

performance. R8 (470K) was 36% high. All other resistors were

OK.

-

The AC switch and volume control did not operate

correctly. This was likely what killed the radio, since no other

serious problems were found. If this issue could not be resolved, it would

be a showstopper!.

Restoration Strategy

Since almost all of the original parts were still in place I decided to try and

maintain the

original chassis appearance to the extent possible. All

original capacitors would be rebuilt in their original cases (restuffed). Any parts replaced in

servicing would be replaced with original parts if available. Any out of tolerance

resistors would be replaced with the same types if available. When I replace a component, I

always remove the original part completely from a terminal. Other good components connected at the terminal are protected from heat using old medical

clamps (hemostats). Excess solder is then removed using a solder sucker in order to

expose terminal holes for reattachment of the rebuilt or replaced component.

I assume that all paper and electrolytic capacitors are leaky and thus should be

replaced (I always "restuff" the original components if possible). I

do not replace mica capacitors, but may test them in place if possible (usually

this requires disconnecting one end of the capacitor).

Repairs

Volume Control and Switch

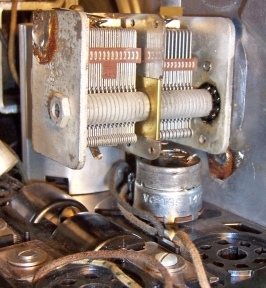

The volume control and switch assembly was unique to this type

of radio and cannot be replaced by the usual type of replacement control. Key

portions of the control, such as the housing and shaft bushing, are actually molded as part of the chassis! My

IRC Replacement Volume Control reference manual states "Obtain replacement

from manufacturer." The volume control element has only a thin layer of

carbon and is thus easily damaged. The rotating element does not contact the

resistance element directly. Rather, there is a thin flexible circular steel spring that is compressed against the resistance track by the

rotating element. As found, there was a bent or indented area found on the circular

spring. In addition, the control shaft was not securely attached to the rotating

element. It appeared originally to have been pressed in. This

allowed the control shaft to rotate continuously. Since the shaft also

operates the AC switch, this would have to be repaired somehow.

The carbon resistance element measured a reasonable resistance

of 545K (spec is 500K), although there were obvious areas of wear and damage. My

first attempt was to repair the control, since replacement would have been

impossible. The rotating member and some fiber washers were removed

for access to the circular spring by removing a clip on the top of the chassis. The kink

in the contact spring was straightened as best I could using flat nose pliers.

The underside of the contact spring was cleaned using lacquer thinner and a

Q-tip. The carbon resistance track was NOT cleaned. I have learned the

hard way that any attempt to clean this type of control will destroy the

resistance element. The control shaft and rotating member were reattached by

soldering them together. The control was then reassembled and tested. It

was tested by connecting a 9 volt battery across the resistance element and measuring the

voltage on the center lug using an analog VTVM as the control shaft was rotated.

There was a dead area in the rotation, and the VTVM pointer jumped around. So the control would somehow have to be

replaced.

The switch mechanism was originally a set of spring contacts

attached to the bakelite chassis that were operated by a cam molded on the

bottom of the volume control knob. After taking some measurements, I

determined that there was not enough room to mount a normal type volume control

with an attached switch. There was only about 7/8" clearance between the top of the

chassis and the tuning capacitor. There were only a couple of options that I

could think of:

-

Install a normal IRC type Q (or equivalent) 500K volume control on the top of the

chassis without an attached switch and install a switch in the AC line

cord. Even this could be a problem since the normal shaft provided

with IRC type Q-controls may not be compatible with the volume control knob.

-

Search my junk box of controls for a more suitable replacement

control with switch that will fit and which has the correct length split-splined shaft.

I have a collection of used controls with and without switches

from scrapped radio and TV chassis, or purchased at swap meets. I did find a couple of candidates that

might fit, but just

barely! Both were 500K and tested good after cleaning. Both had split-splined

shafts. One shaft was slightly longer than the other. In order to use this

strategy, I had to remove the existing control shaft bushing and also enlarge

the chassis hole to 3/8". The chassis is quite thin at this point, so

this was a dangerous operation. The tuning capacitor and dial assembly was

removed for access. I was able to enlarge the hole to clear

the replacement control using a set of progressively larger drill bits.

The shaft bushing on top of the chassis and the short bakelite boss on the other side of the chassis

were removed using

a Dremel tool and cut-off disc as a grinder. Both replacement candidate

controls were mounted and checked for fit. I had to cut off most of the AC switch

lugs in order to clear the tuning capacitor rotor directly above the control.

The knob was refitted to check for the best shaft length.

The replacement control seemed to work OK, but compromises were

required. First, since the replacement control was mounted on TOP of the

chassis, the direction of rotation (minimum to maximum volume) was opposite of

the original control. Since the control is operated by a thumb wheel

rather than a knob, this is not a major issue. Also, the three terminal lugs

(now on TOP of the chassis) are in the opposite order from the original, and

also on the other side of the chassis. So some rearrangement of wiring was

necessary.

At this point I abandoned my original objective of restoring

the original chassis appearance and decided to simply get the radio working.

Resistors

The radio used some older style "dogbone" type

resistors as well as 20% tolerance carbon composition resistors. IR4 (2.2 meg) and R8 (470K) were both 1/4 watt dogbone types, and were

replaced with normal 1/2 watt carbon composition types. Fortunately all of the wire wound resistors in the radio were

OK.

Wax/Paper Capacitors

All except one of of the original Zenith paper capacitors were replaced with

modern axial 630 volt film capacitors. The placement of the original capacitors

were very critical since there is very little space under the chassis. They were

not restuffed. One metal cased capacitor was above the chassis and thus

visible. This one was restuffed.

Filter Capacitor

The original tubular filter capacitor was still in place. It was

a three section capacitor with wire leads. The original tubular capacitor was

removed from its metal case, but the original wire leads were retained and

re-used. New axial electrolytic capacitors were used to replace the original

capacitor. They were insulated using shrink tubing and re-installed in the

original metal container.

Other Repairs

The line cord was replaced by a modern brown vinyl cord.

Testing and Alignment

Once the radio had been reassembled and the tubes installed,

the radio was powered up using a fused Variac. The radio came alive and

actually worked. The set was then aligned. The radio worked, but the

performance was nothing to write home about. Based on my experience with

this radio and my Zenith 4K-402D, I

will certainly avoid buying any more of this type of radio!

Restoration Results